The Enlightenment, Utopianism and Modern Education

Part 2 of The Globalist Education Series

Harvard historian Charles Homer Haskins informs us that the modern university is the product of the Renaissance and “is the lineal descendent of medieval Paris and Bologna.”1

Prior to the upheavals of the nineteenth century, education in the West was generally defined as the cultivation of an individual’s mind and innate talents across an array of subjects, providing the individual with the required tools to learn and comprehend objective truth.

Since the fall of Rome in the fifth century, the universal Christian Church served as the sole proprietor of what minimal education was available in Europe. Over time, the Church established the cathedral and monastery schools of the Middle Ages and, ultimately, the great universities of Western Europe.2

In practice, however, few forms of later schooling would be the intense intellectual centers these were. The Seven Liberal Arts made up the main curriculum; lower studies were composed of grammar, rhetoric, and dialectic. Grammar was an introduction to literature, rhetoric an introduction to law and history, dialectic the path to philosophical and metaphysical disputation. Higher studies included arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy. Arithmetic was well beyond simple calculation, entering into descriptive and analytical capacities of numbers and their prophetic use (which became modern statistics); geometry embraced geography and surveying; music covered a broad course in theory; astronomy prepared entry into physics and advanced mathematics.3

Author and educator John Klyczek explains that a classical education based upon Greek philosophy, beginning with the Trivium of grammar, dialectic and rhetoric, gifted those fortunate enough to receive such instruction with the “thought-architecture of human consciousness which predicates the art of thinking.”4

As the foundation upon which the political institutions of Western civilisation were to be built, the skills learned by way of the Trivium allowed for the development of Western law and political representation within the Westphalian nation state.

As a higher form of political organisation beyond tribalism, the nation state facilitated great economic, social and cultural development within the West. This ensured a level of stability whilst allowing for the construction of a coherent national culture and meaningful citizenship for the interconnected communities who made up the national family.

Due to the underlying culture and high level of social trust, the citizens of several European nation states came to develop a greater sense of individualism and developed market economies which led to more rapid industrialisation and the accumulation of capital for investment.

Although life was far from perfect, Europeans generally came to enjoy individual freedoms unheard of in the oriental despotisms of the East where vast empires ruled over great numbers of humanity born into bondage and a stagnant social hierarchy.

The birth of scholasticism, the analysis and presentation of Church teachings in scientific terms between the eleventh and fourteenth centuries, saw schools become more concerned with rationality and logic rather than emotion.

Scholasticism became the basis of the education given to the upper classes who received intensive instruction involving rigorous discipline and moral formation.

The place reserved for classical philosophy within Western education served as the bridge to Greece and Rome. These prior civilisations were intensely invested in the correct ordering of society in relation to the cosmos whilst providing for the nourishment of the human soul.

The universalism of Christianity further developed the paganism of the Platonic and Aristotelian philosophic tradition by emphasising the equality of mankind and the unique value of the human soul in the eyes of God.

This search for equality, in the hereafter and in the physical world, can be traced to the evolving social message of a succession of Hebrew prophets and Jesus Christ. The pursuit of greater equality has also provided a basis for much utopian thought during the modern period, particularly through the promise of salvation by spiritual and social deeds in the physical world.

Jesus’ rebuke of the Pharisees and of the mammonism of the time was radical and has animated in numerous ways successive revolutionary movements, even those of a secular nature which have been generally hostile to Christianity. We are speaking here most obviously of the secular ideologies of Marxism and the modern progressive creed which will be recurring themes in our analysis of Western thought and its relationship to Western education.

In his extensive analysis of the history of Western thought, philosopher Eric Voegelin came to the conclusion that the Enlightenment reset the centre point of Western history from the transcendental figure of Christ to humanity itself.5 In essence, man substituted God for himself.

The symbolic language of Christianity was then historicised by the rationalism of the Enlightenment and reduced to myth. The symbols of Christianity, so transformed, were now rendered inaccessible to the consciousness of the new man whose life was increasingly focused on the temporal realm and material “progress”.

Voegelin describes this loss of connection to the transcendent as the “crisis” which has since plagued Western civilisation.

Following the onset of the “crisis”, Western man has attempted to replace his lost connection to the transcendent through the material realm, initially through the naturalism and scientific progress of the Enlightenment, and later through the establishment of secular ideologies.

This rational and materialistic replacement for the transcendent saw the idea of material and social progress become the focus of man’s better instincts. The pursuit of expanding levels of scientific and economic development required that man be understood on these terms, but how should progress be measured in relation to man and his material improvement?

During the Enlightenment, the concept of the “pleasure-pain mechanism” became acknowledged as the only source of experience.

Under this utilitarian logic, which presaged the nineteenth century Marxist assault on being, the concept of the “greater good” was determined to be the greatest material pleasure for the greatest number.

Man was now reduced to a stimulus-response mechanism whose passions, particularly the will to power, assured that his highest thoughts were the pursuit of individual “happiness”.

The growth of the soul through an internal process which is nourished through communication with transcendental reality is replaced by the formation of conduct through external management. Here is the origin of the managing and organizing interference with the soul of man which, from the position of a spiritual morality, is equally reprehensible in all its variants; whether it is the propagandizing formation of conduct and opinion through such political movements as the Communist or National Socialist or an educational process which relies on the psychology of conditioned reflexes and forms of patterns of social conformance without raising the question of the morality of conformance.6

In his study of the relationship of Enlightenment philosophy to authoritarianism, philosopher Isaiah Berlin summarised the morality of the new scientific and naturalistic paradigm of the Enlightenment thusly:

Ethics is a kind of technology, for the ends are all given. If you ask ‘Why should we do what we do?’ the answer is: ‘Because we are made to do it by nature, because we cannot function otherwise.’ If the ends are given there is no need to investigate those further. The only business of the expert, or the philosopher, is simply to create a universe in which the ends which men have to seek because they cannot help it are obtained with the least pain, most efficiently, most rapidly, most economically.7

The role of the “manager”, and the related roles of legislator and educator, will be central to our analysis of modern education.

Another line of analysis will be the concept of the individual and his rightful representation in society which is quite unique to Western civilisation and stands amongst its greatest gifts to humanity.

Emanating out of the “Christian and medieval aristocratic tradition”, the concept of equality became during the eighteenth century “the idea of the equal pleasure-pain mechanisms who all are engaged equally in the pursuit of happiness.”8

Equality in the modern sense is thus defined, most reductively, as the pursuit of pleasure and the minimisation of pain, in other words, the equal satisfaction of man’s passions for all rather than the pursuit of genuine metaphysical good.

In order to realise this intangible equality, organised revolutionary mobs and political pressure groups have continued to gather and to demand greater social and economic power over others.

In the hands of such activists, education becomes a mechanism of social transformation to create the imagined utopia whilst serving as a means of forming a sense of ideological unity between people, amongst whom traditional bonds have been dissolved.

With all of this in mind, we will now discuss the revolutionary concepts that began to be introduced into education since the Enlightenment through the thinking of influential philosophers and educational theorists such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the utopians of modernity.

This will provide an introduction to the progressive philosophy of education which is most intimately associated with the construction of a new man for a new age.

From Enlightenment to Utopia

A series of dedicated attempts at replacing the classical conception of education began in the West during the nineteenth century. The emergence of this progressive and managerial type of education, involving the application of the tools of the new sciences of psychology and economics, has accompanied the utopian project of creating an integrated world society.

If education can liberate the individual, it must also be understood that in the wrong hands education can become a means to ideologically indoctrinate and even render the individual an unthinking being, dependent on others for their opinions and legitimacy.

Since the beginning of modernity and humanism, modern man has been increasingly redefined as a consumer and an economic unit—homo economicus—and secondly as an agent of social change to facilitate his own degraded transmogrification.

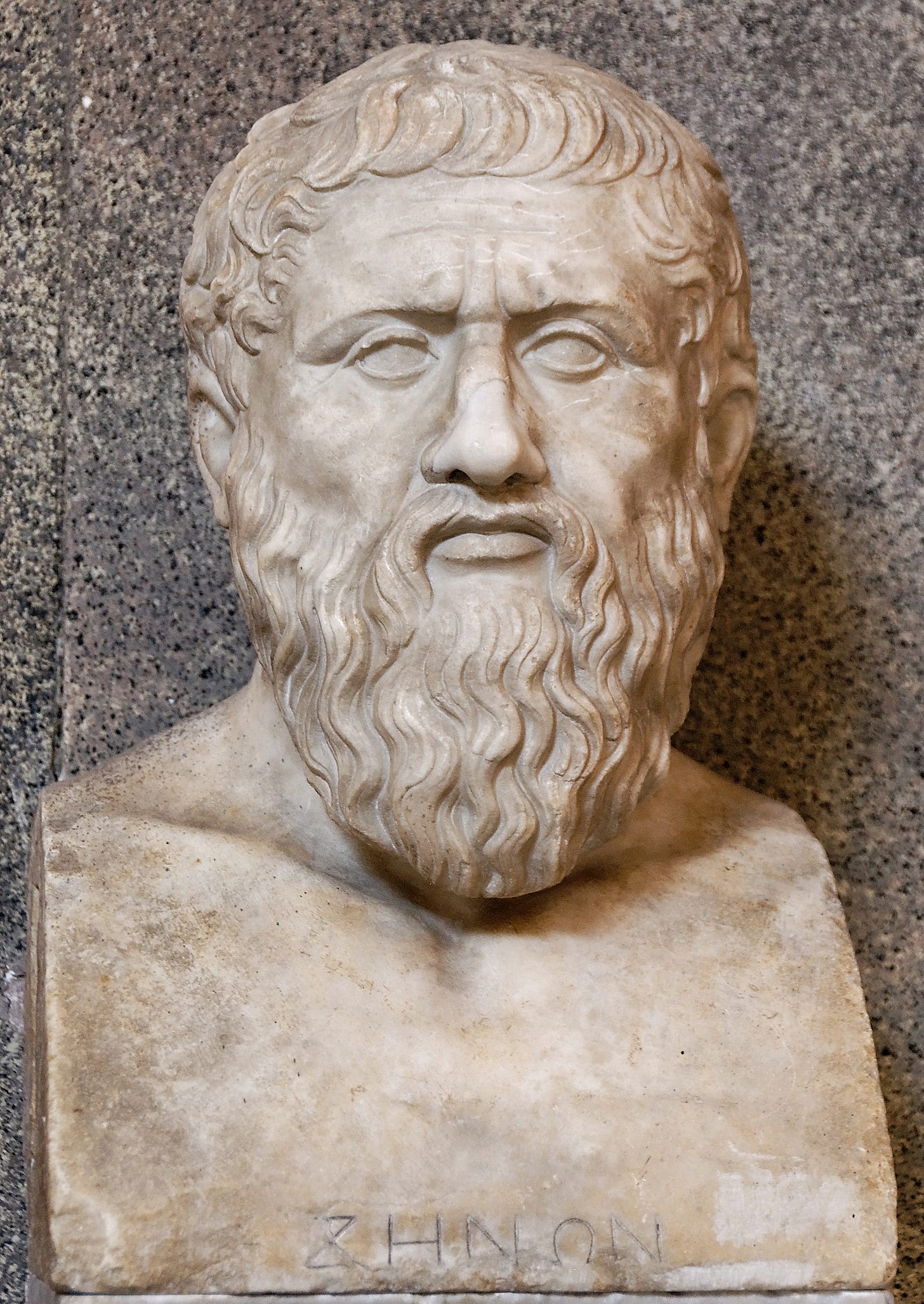

Much of the new education that emerged in the nineteenth century can be traced back to Plato and to the Enlightenment, the emphasis being on the levelling of mankind into one manageable organism.

Although premised upon how to structure an ideal society of perfect justice and harmony, Plato’s Republic also serves as the original manual on establishing an authoritarian society governed by a ruling elite.

Both Plato and Aristotle linked education to social and political ends, a fact which makes them progenitors of the later utopian and progressive educators of modernity.

However, the classical view of the world as an “ontic logos” within which objective truth and political harmony is discoverable, had already been left behind with René Descartes, the first modern philosopher and mathematician who upended centuries of Western thought with his definition of reason derived from physical measurement of sensory data.

Once cosmic order was no longer seen as embodying either the Platonic Forms or Aristotelian species and forms that which lay outside the early Christian ‘inner man’ had to be rewritten. This rewriting saw the external as an extended substance, ‘World or Universe.’ The human body marked the judicial horizon between interior/exterior realms. The World as extended substance did not hold pre-existing Ideas and Goodness that one journeyed through the inner man to arrive at. Aspects of the whole were not borne into the parts and the integrity and meaning of the parts did not carry forward to become an integral part of the whole. The body and the World were quantities open to theorization as to what they did or did not hold or as to what laws structured them.9

The thinkers of modernity, therefore, were living in the wake of a revolution of consciousness and held an entirely new conception of the world which now held no innate goodness or meaning. Now, everything was matter. Only science could be trusted to explain the world and the relationships between different things.

The standard or norm for Truth now lay within the procedures themselves, not on a shelf waiting for the person to turn toward it.10

Man was also reduced to matter but his mind and the awareness of his existence made him at least human. Mind provided a means to conceive of new ideas and to imagine entirely new worlds which could be brought into existence by the correct ordering of processes and the manipulation of matter.

The work of David Hume, John Locke and the French Encyclopédistes sought to establish new rational definitions of man and to assemble a single body of scientific knowledge that could replace the earlier knowledge which was now deemed to be irrelevant. The wisdom of antiquity and Christianity began to fall into a state of disrepair as the new modernist intellectuals began categorising man.

This new scientific spirit led to the establishment of a reductive view of man who was now increasingly defined as a series of sensory mechanisms. This understanding of man directed power to those with their eager hands on the controls, including the educator.

Inspired by the earlier work of Locke, Claude Adrien Helvétius, a member of the circle of French Encyclopédistes, produced a “généalogie” of the human passions which concluded that “Moral man is altogether education and imitation.”11

For Helvétius, “the educator takes the place of God: where the grace of God has failed, the educator may achieve results by a judicious application of the psychology of conditioned reflexes.”12

Berlin provides a summary of Helvétius’ plan for education which includes a cynicism towards the teaching of history or the teaching of classical languages. “All interest is practical interest. What people must be taught, consequently, are the sciences and the arts, and among the arts is that of being a citizen. There is to be no ‘pure’ learning; for nothing ‘pure’, without useful application, is desirable.”13

Voegelin argues that in Helvétius can be found “the origin of the artificiality of modern politics as engendered through propaganda, education, reeducation, and enforced political myth, as well as through the general treatment of human beings as functional units in private enterprise and public planning.”14

Berlin explains that the “physiocratic” philosophers of the eighteenth century, including Helvétius, viewed legislation as “the translation into legal terms of something which is to be found in nature: ends, purposes.”15

Who better than the scientist to function as the managers, educators and legislators?

Scientists know the truth, therefore scientists are virtuous, therefore scientists can make us happy, therefore let us put scientists in charge of everything. What we need is a universe governed by scientists, because to be a good man, to be a wise man, to be a scientist, to be a virtuous man are, in the end, the same thing.16

Helvétius also provides the most direct point of origin for the thought of the utilitarians such as Jeremy Bentham and the dialectical materialism of Karl Marx who desired to lock man inside of a prison of matter whilst transforming his very being through the eschatological role play of revolution and rebirth.

Utopianism erupted within this new world of scientific rationalism, holding out the promise to create a new world and a perfect man who was now free from the constraints of the old one and liberated from his own conscience.

In his classic study of utopian thought, Joyce Oramel Hertzler described Plato and later utopians as “the prophets of the modern eugenics movement”17 owing to their shared desire to control and manage carefully the procreation of the individual via the state which was directed by an elite who had achieved a level of greater perfection. The connection between utopianism and utilitarianism is also apparent.

Plato’s Republic provided a foundation for the utopian texts of the early modernists, including those of Thomas More, Francis Bacon and James Harrington, all of which articulated plans for a future ideal society amidst the upheavals of the Enlightenment and the accompanying delegitimisation of the old feudal order which accompanied the rise of republicanism.

These writers were undoubtedly brilliant men who attempted to grapple with a multitude of social ills, including the poverty and appalling living conditions of the poor.

Each blended Christianity with Greek philosophy to some extent. However, the limitations of such utopianism are apparent when we consider their idealistic assumptions about human nature and when we read their work in the context of the ensuing centuries of rapid social and technological change which render them outdated.

Their imagined utopias range from the constitutionalism of Harrington, whose The Commonwealth of Oceana was written in the context of the Puritan Revolution with its emphasis on the individual and property, and the technocracy of Francis Bacon whose New Atlantis emphasised the rule of scientific experts, whilst foreshadowing the later technocratic and progressive thought of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries with its communistic collectivism.

Thomas More coined the term utopia and clearly never believed that such a society could exist.

Subsequent utopians saw in the establishment of a mandatory educational system controlled by the state, the appropriate means to ensure the socialisation of all citizens. Moreover, these systems would provide a means to identify and cultivate what Plato described as the “guardian” class who were responsible for directing society.

Hertzler argued that the guardians represented the emergent superior man, the prototype of the later supermen “expressed in Carlyle’s ‘hero,’ Schopenhauer’s ‘genius,’ and Nietzsche’s ‘superman.’”18 To this we might add the transformed man of Marx whose rebirth, he foretold, would follow the vanquishing of the old corrupt world of the bourgeoisie.

Plato’s embrace of female equality and his jealous opposition to the family and its independence from the state, render him an antecedent to social revolutionaries such as Marx’s collaborator Friedrich Engels who published The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State in 1884 in which he articulated similar sentiments towards women and the Western family unit in the language of Marxist analysis.

The rediscovery of Plato during the Renaissance provided much impetus for the utopian and reformist impulse in the West. The introduction of the printing press, the great expeditions by European explorers to the New World, and the revelations of Copernicus concerning the size and context of planet Earth in the cosmos informed a determination to make the world anew.

Men believed that a new universe had been born, and that they were to produce a new method of life, purged of the imperfections of the old. The intellectual stimulation of a new culture and a new social philosophy coming into a discontented world, which was then reënforced [sic] by the physical revelation of new earthly and heavenly bodies, gave to men the conception of human perfectibility to occur in an ideal world...19

The scientific rationalism of Enlightenment thought had slid the door ajar for utopian idealism but a Genevan intellectual called Jean-Jacques Rousseau was embarking on his own journey to address the “crisis” in Western civilisation. Central to this philosophy would be his own programme of education.

Rousseau and the Enlightenment

The Enlightenment idealism associated with the advent of modernity tended towards the pursuit of expanding levels of equality and universalism.

This faith in universal equality fed into the existing belief amongst the men of science that man was matter and could be altered and improved through the control of his environment and social conditions.

As such, the Enlightenment inaugurated a naive faith in the malleability and perfectibility of human nature as well as a derogation of the role of the individual’s conscience.

American intellectual William Kirk Kilpatrick argued that the Enlightenment, with its objective of human happiness and improved material conditions, can be credited with the attempt to establish morality on a rational and, later, a romantic basis. Both of these forces, he argues, “swept away centuries-old habits of thought, and swept the Western world into the modern age.”20

This radical departure was premised upon finding “principles of ethics which could be agreed to by all men and women, no matter what their class, culture, or religion. These principles, because they were established on reason, would be able to stand on their own without the assistance of church or commandments.”21

David Hume, Thomas Hobbes and John Locke provided the framework for the liberal democratic order which came to dominate the Anglo-American world. It is from this train of thought that the social science of economics was to flourish and, along with it, a new kind of man, the individual who was guided by little more than the fear of death and a desire to obtain material comfort.

Hobbes and Locke supposed that, although the political order would be constituted out of individuals, the subpolitical units would remain largely unaffected. Indeed, they counted on the family, as an intermediate between individual and the state, partially to replace what was being lost in passionate attachment to the polity.22

Modern Western politics was borne from this constellation of minds which saw Hobbes and Locke establish a practical replacement for the old order premised upon the innate rights of the individual derived from natural law.

Locke provided the doctrinal basis for the United States Constitution as a place for the individual to pursue his enlightened self-interest. In doing so, modern man was to be a purely economic and rational being liberated from ties of blood and tradition.

Building on the work of Locke, Helvétius, an atheist, worked out his schema for modern society in which the individual is disconnected from transcendental salvation and reduced to his physical senses and his reactions to those senses. Mankind was now to be “split into the mass of pleasure-pain mechanisms and the One who will manipulate the mechanisms for the good of society.”23

The American Revolution separated religion from government whilst initiating a pragmatic solution to the problem of political representation which ensured a significant level of individual freedom and minimal governmental power. Traditions could continue to be upheld by way of the family and wider community which were to be left largely unmolested by the state.

In response to Enlightenment rationalism the “Romantic movement rediscovered art, mystery, and irrationality.”24 Most importantly, it rediscovered the emotions and used them to construct an entirely new way of defining morality.

The chief prophet of the Romantic movement was the Swiss-born philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. It was Rousseau who developed the doctrine of natural goodness in its most attractive form. The theory proposed that in a natural state children could be counted on to develop natural virtues. This would happen in an almost automatic way, like the process that occurs when a bud unfolds into a flower. Since all individuals are different, each child would develop differently. But all would unfold in a positive direction: that is, into roses, marigolds, and sunflowers—not into poison ivy or skunkweed.25

The assumption that man, in his natural state, was inherently good demanded that institutions such as schools be constructed in accordance with this idealistic assumption. Institutions such as the family would also need to be reformed, or even replaced by something new entirely to ensure the child was not influenced by the traditional values of the older society.

These are the basic assumptions of the subsequent utopian socialists of the early nineteenth century who took Rousseau as a starting point for their respective movements and of contemporary social revolutionaries, many of whom insist that their ideas are in some way novel.

Isaiah Berlin argues that Rousseau, in rejecting the pragmatism of earlier Enlightenment thinkers such as Hobbes and Locke, established an insurmountable paradox between “the absolute value of freedom and the absolute value of the right rules.”26

The problem must be viewed in such a way that one suddenly perceives that, so far from being incompatible, the two opposed values are not opposed at all, not two at all, but one. Liberty and authority cannot conflict for they are one; they coincide; they are the reverse and obverse of the same medal. There is a liberty which is identical with authority; and it is possible to have a personal freedom which is the same as complete control by authority. The more free you are, the more authority you have, and also the more you obey; the more liberty, the more control.27

Rousseau, like most earlier Enlightenment thinkers before him, believed that nature was characterised by harmony. In nature could be found rational principles. If one man’s ends conflict with the ends of other men, then the ends themselves must be unnatural and therefore wrong. The individual will and the general will of others should be in alignment. If they are not, then the man not in alignment with the general will must be wrong and corrupt.

Natural man is assumed to be innately good and if all men are natural men, then the combined general will of those men will also be innately good.

Those who have followed in the footsteps of Rousseau have sought to construct a new society by force of will, to implement a year zero and bring about a new age. In doing so, they misconstrue Rousseau’s genuine humanity and desire to cultivate the higher virtues of man.

Indeed, the first truly progressive educational philosophy can be traced directly to Rousseau who desired a more permissive, child-centred approach to education, which emphasised the socialisation of the child into the broader society which was to replace the family and village life of the past.

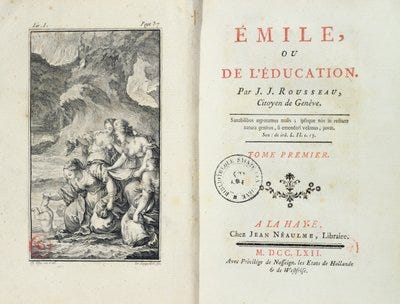

The publication of Rousseau’s Émile, or On Education in 1762 focused a movement of protest against the formality and ostentatiousness of elite French society and provided the basis for a new type of education derived from the naturalism of the revolutionary French Enlightenment.

Rousseau viewed Émile as his most important work. Indeed, the main reason for Rousseau’s enduring influence upon progressive educators is found in Émile where “Rousseau most fully explains and defines his well-known view that man is by nature good but corrupted by society.”28

In this Rousseau favours what he calls ‘negative education’, where the child is not controlled, directed, admonished at every turn but instead provided with an environment and resources in which the naturally healthy and ordered course of development of their body, feelings and understanding is allowed to unfold at its own pace in accordance with its own proper dynamic and they are able to grow to maturity whole and happy. The child’s own emerging interests should be supported and enriched, not be subjected to impositions and requirements.29

Émile and the other writings of Rousseau became instantly influential in England “among those concerned with problems of science, industry, public health and education, and philosophical speculation” including the membership of the Birmingham Lunar Society and the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society.30

Many of these English radicals and reformers were well familiarised with their French contemporaries and several wrote treatises on education. Amongst this grouping we can include Irish landlord Richard Lovell Edgeworth, David Williams and Thomas Day, all of whom can be considered the most significant English applicants of Rousseau’s philosophy of education.

Birmingham Lunar Society founder, Erasmus Darwin, was another notable Francophile of the period who personally met Rousseau and was inspired to publish his own ideas on education.31

Darwin is more commonly known as the grandfather of Charles Darwin and Francis Galton, the pioneering eugenicists who provided a generation of nineteenth century scientists and philosophers with an alternative basis upon which to base human existence through the theory of evolution.32

Following in the wake of Émile came a slew of romantic accounts of native tribes in far-flung corners of the world. These representations of man in his natural state, a central symbol on which Enlightenment thinkers such as Locke and Hobbes had theorised, were now romanticised by utopians and revolutionaries. These tales fed the appetites of affluent Western audiences for romantic escapism and helped establish the growing cult of the noble savage which lionised the purity of primitive societies over the corrupted West.

This tradition of constructing idyllic narratives around primitive societies, unencumbered by the imperialism of Western cultural or social mores, continues to occupy the minds of a sizeable cohort of the Western intellectual class and served as an antecedent of the Sexual Revolution of the 1960s with its promises of free love divorced from responsibilities.

In addition to his contribution of the social contract, Rousseau had codified a philosophy of education that influenced the utopians and early progressives of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. We will discuss some of these followers over the coming paragraphs.

Most importantly, Rousseau had created an addictive formula for how to address in the temporal realm the “crisis” that underlies the modern period as articulated by Voegelin. If a child could be educated so that his innate goodness was best developed, then maybe a world of liberty and equality, the idealistic promises of the Enlightenment, might finally be realised.

Many others were paying attention and a number of them were determined to put the ideas of Rousseau into practice in the classroom.

Rousseau and Progressive Education

The progressive approach to education has been documented since the 1750s in countries such as England where there is a long tradition of progressive schools.33

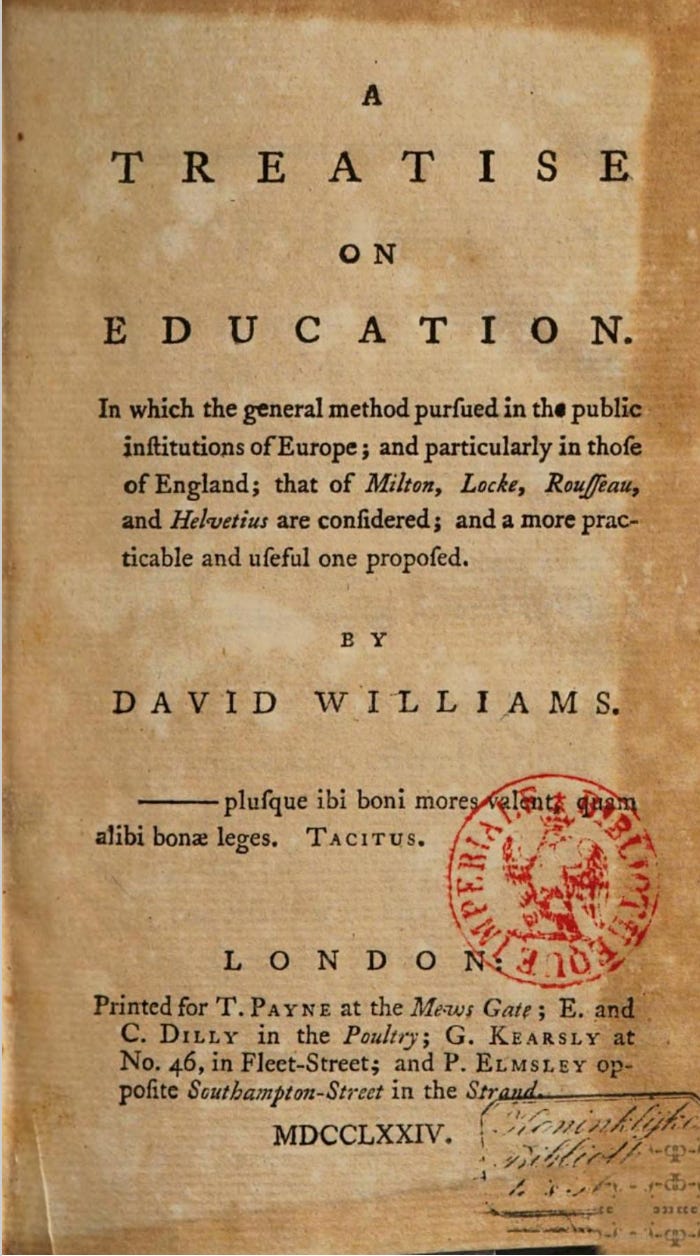

Indeed, David Williams, a Deist “Priest of Nature” who was a friend of Benjamin Franklin and numerous French Revolutionary leaders, perfectly encapsulated “the classic case of the political radical turned educational reformer” when he opened a short-lived school based on Rousseau’s philosophy in Lawrence Street, Chelsea in 1773.34

His experiments in the curriculum and teaching methods anticipated nearly all the innovations that claimed originality in the nineteenth or even the twentieth century. This was particularly true of the introduction of a wide range of subjects, the emphasis on science as opposed to classics, the introduction of new subjects such as economics and sociology into the curriculum, the integration of subjects, natural methods of language teaching, the project method, the concentric method of geography teaching, and so on.35

Whilst being the first to make a consistent application of the basic principles of Rousseau’s Émile in a classroom setting, Williams was also an innovator through his use of “psychological theory”.

“With Rousseau as a guide he tried to understand the psychology of the child by means of close observation, and to base his teaching upon his theories.”36

In addition to observing the child and allowing him to learn from his experiences, the role of the teacher being the “management of the child’s natural activities”, Williams provides us with “the earliest example of successful group methods in education.”37

In 1774, Williams published A Treatise on Education in which he constructed upon the educational philosophies of his predecessors, John Milton, Locke, Helvétius and Rousseau.38

Williams was also a founding member of the Club of Thirteen which flourished during the 1770s and 1780s. An international coterie, the Club was influenced by Rousseau and enjoyed direct correspondence with American revolutionaries such as Founding Fathers Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson.39 The Club was made up primarily of members of the Birmingham Lunar Society and also enjoyed relations with German and other European radicals of the time who frequently met in Williams’ chapel and other locations.40

Williams was later made a French citizen and “helped in the drawing-up of a new constitution, undertook diplomatic missions, and was welcomed to discussions with French philosophers and politicians.”41

Many English radicals ultimately distanced themselves from the French Revolution following the ensuing violence, but a shared naturalist religion, and their belief in the cult of reason, served as an embryonic representation of the globalist ideology which is the result of the “crisis” of Western civilisation.

Pioneering British feminist and mother of Frankenstein author Mary Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft, was amongst the Francophile English radicals who soured once the bloodshed had erupted but retained her “faith in social progress and individual rights that the Enlightenment seemed to presage.”42

Wollstonecraft and her husband William Godwin, a leading utilitarian theorist, also wrote treatises on education based largely on the work of Rousseau.43

In articulating his desire to go beyond the liberal political structures of Hobbes and Locke, Rousseau had argued that the state must take a far greater role in forming individual citizens into a cohesive whole, arguing that the legislator must,

so to speak change human nature, transform each individual, who by himself is a perfect and solitary whole, into a part of a greater whole from which the individual as it were gets his life and his being; weaken man’s constitution to strengthen it; substitute a partial and moral existence for the physical and independent existence which we have all received from nature. He must, in a word, take man’s own forces away from him in order to give him forces which are foreign to him and which he cannot use without the help of others. The more the natural forces are dead and annihilated, the greater and more lasting the acquired ones, thus the founding is solider and more perfect; such that if each citizen is nothing, can do nothing, except by all the others, and the force acquired by the whole is equal or superior to the sum of the natural forces of all the individuals, one can say that the legislation is at the highest point of perfection it can attain.44

Thus, Rousseau provides an origin point, not only for progressive education, but for the concept of modern culture which provides for a deeper bond amongst men, as opposed to the merely utilitarian and economic basis of earlier Enlightenment thought.

The declared rights of the individual provided for by Hobbes and Locke were augmented and provided with deeper meaning through culture. Through culture, the political institutions of the Enlightenment might inherit a perfected people who were united as part of a larger family and trained to have the required social and political skills for meaningful citizenship.

From his deification of human freedom as articulated in The Social Contract, “Rousseau gradually moves towards the notion of the general will as almost the personified willing of a large superpersonal entity, of something called ‘the State’, which is now no longer the crushing leviathan of Hobbes, but something rather more like a team, something like a Church, a unity in diversity, a greater-than-I, something in which I sink my personality only in order to find it again.”45

The power enjoyed by the legislator in this arrangement also provided the potential for the suppression of the individual in a machine that denied him the intellectual gifts of his own mind and the moral gifts of his own conscience. Like earlier Enlightenment thinkers, Rousseau had good intentions but he represented, inadvertently, another step towards a purer form of social control, the central objective of the progressive educators of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Rousseau’s means of solving the paradox of individual liberty and the need for authority produced “the monstrous paradox whereby liberty turns out to be a kind of slavery” whereby man, having lost his political and economic liberty to the state “is liberated in some higher, deeper, more rational, more natural sense, which only the dictator or only the State, only the assembly, only the supreme authority knows, so that the most untrammelled freedom coincides with the most rigorous and enslaving authority.”46

As the grandfather to all revolutionaries and, in particular, to the utopian socialists of the early nineteenth century who were imbued with the desire to transform society via the control of culture, initially within the confines of their experimental schools, Rousseau is the clearest originator of progressive education which is centrally interested in forming the individual into a suitable social unit.

Rousseau used the term “bourgeois” to describe modern man, a denatured creature whom Rousseau desired to renovate by rekindling his natural goodness as an autonomous and good person.

Allan Bloom explains how Rousseau’s bourgeois man is “the man motivated by fear of violent death, the man whose primary concern is self-preservation or, according to Locke's correction of Hobbes, comfortable self-preservation.”47

Rousseau established the dichotomy between bourgeois or economic man, with his desire to subdue and escape from nature, and revolutionary or natural man, who desired to return to nature and find, within its non-judgemental cycles, an idyllic life and his authentic self.

Both tendencies are present in modernity, often within “bourgeois” man himself, with his proclivity to enjoy the material benefits of modernity whilst romanticising the natural world from whose grip he has only recently escaped.

Building on the work of Rousseau, German idealist philosopher Imannuel Kant “undertook a systematic overhauling of Enlightenment’s project in such a way as to make coherent the relationship between theory and practice, reason and morality, science and poetry, all of which had been made so problematic by Rousseau.”48

Kant’s cosmopolitanism and universalism makes him a progenitor of both globalism and modern education, which is largely concerned with creating a new kind of man who will successfully bring about and maintain a global society, the elusive global citizen.

This utopian project exists most vividly in the minds of a relative handful of progressives from the intellectual and economic elite classes of the West whose acculturation within the confines of the modern university has assured that they hold dear these ideals.

It falls upon this same class of affluent Western progressives to manage Western domestic and foreign policy. As such, the relationship established between the West and the more traditional civilisations and societies outside is a unidirectional one, consisting of social and economic sacrifices by the West in the name of alleviating past sins, with the hope of establishing a global society of peace and equality in the distant future.

Like Rousseau and Kant, German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche also warned that modern man was disconnected from his humanity, arguing that he was sure to fail in his endeavour of founding nations on Enlightenment rationality alone.

For Nietzsche, the existence of creativity meant that a universal understanding of man based on merely rational principles was impossible.

Allan Bloom summarised Nietzsche’s attempt to save the Greek tradition from the academics of the modern university and his desire to reconnect with the sublime through Greek poetry and the development of culture.

The discovery of culture as the element in which man becomes himself produces an imperative. Build and sustain culture. This the scholars cannot do. Culture is not only the condition of life, it is the condition of knowing. Without a German culture, the scholar in Germany cannot confront other cultures.49

The observation that culture cannot be understood properly without the nourishment and tools only available through the practice of one’s own culture may provide insight into why modern Western intellectuals, suffering from an absence of authentic culture, are unmoored in abstract worlds of relativism and critical struggle sessions when compared to the great minds of history.

Indeed, Plato’s ideas were not predicated upon establishing global civilisations but upon the small city states of the time in which people shared enough commonalities to make consideration of the higher virtues possible, virtues which are totally absent in the post-Enlightenment West with its materialistic greed and performative pursuit of equality.

Following Nietzsche came a slew of others bearing warnings of Western decline.

Nietzsche examines the patient, observes that the treatment was not successful, and pronounces God dead. Now there cannot be religion; but inasmuch as man needs culture, the religious impulse remains. No religion but religiosity. This suffices Nietzsche’s analysis of modernity, and, unnoticed, it underlies the contemporary categories of psychology and sociology. He brought the religious question back to the center of philosophy. The critical standpoint from which to view modern culture is its essential atheism; and that more repulsive successor of the bourgeois, the last man, is the product of egalitarian, rationalist, socialist atheism.50

Nietzsche’s recognition of the importance of culture and his bemoaning of the loss of connection to the transcendent brings us back to our opening examination of the “crisis” as articulated through the work of Eric Voegelin. The “isms” of modernity are but substitutes for the religious impulse which has been removed from the centre of Western civilisation, but remains roaming around, looking for a cause that it can animate.

We have discussed the emergence of a new secular and materialist consciousness during modernity which found man embark on a series of utopian and revolutionary attempts at finding meaning, following man’s transformation to matter by Enlightenment rationalism.

This has led us to analyse the implications for the political and social structures associated with the Enlightenment, including the development of modern education as a means of constructing an ideal citizen for an ideal society which emerged out of Enlightenment philosophy and, most relevantly, Rousseau.

In the next essay, we will explore these ideas through the lens of Gnosticism.

Charles Homer Haskins, The Rise of Universities, 3.

For a detailed history of the university see Charles Homer Haskins, The Rise of Universities.

John Taylor Gatto, The Underground History of American Education: A Schoolteacher’s Intimate Investigation into the Problem of Modern Schooling—Author’s Special Pre-Publication Edition, 14.

John Klyczek, School World Order: The Technocratic Globalization of Corporate Education, 326.

See Eric Voegelin, From Enlightenment to Revolution.

Eric Voegelin, From Enlightenment to Revolution, 70.

Isaiah Berlin, Freedom and Its Betrayal, 15.

Eric Voegelin, From Enlightenment to Revolution, 72.

Michael A. Peters ed., Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory, 111.

Michael A. Peters ed., Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory, 111.

Eric Voegelin, From Enlightenment to Revolution, 48.

Eric Voegelin, From Enlightenment to Revolution, 48.

Isaiah Berlin, Freedom and Its Betrayal, 19-20.

Eric Voegelin, From Enlightenment to Revolution, 50.

Isaiah Berlin, Freedom and Its Betrayal, 15.

Isaiah Berlin, Freedom and Its Betrayal, 25.

Joyce Oramel Hertzler, The History of Utopian Thought, 288.

Joyce Oramel Hertzler, The History of Utopian Thought, 116.

Joyce Oramel Hertzler, The History of Utopian Thought, 125.

William Kirk Kilpatrick, Why Johnny Can’t Tell Right from Wrong and What We can do About it, 101.

William Kirk Kilpatrick, Why Johnny Can’t Tell Right from Wrong and What We can do About it, 101.

Allan Bloom, The Closing of the American Mind, 112.

Eric Voegelin, From Enlightenment to Revolution, 51.

William Kirk Kilpatrick, Why Johnny Can’t Tell Right from Wrong and What We can do About it, 103.

William Kirk Kilpatrick, Why Johnny Can’t Tell Right from Wrong and What We can do About it, 103.

Isaiah Berlin, Freedom and Its Betrayal, 37.

Isaiah Berlin, Freedom and Its Betrayal, 39-40.

Nicholas Dent, Rousseau, 24.

Nicholas Dent, Rousseau, 23.

Stewart & McCann, The Educational Innovators Vol. I: 1750-1880, 30-31.

Stewart & McCann, The Educational Innovators Vol. I: 1750-1880, 30-31.

The subject of evolution and its relationship to progressive ideology and education will be dealt with extensively over a number of future essays in this series.

Stewart & McCann, The Educational Innovators Vol. I: 1750-1880, 3.

Stewart & McCann, The Educational Innovators Vol. I: 1750-1880, 35.

Stewart & McCann, The Educational Innovators Vol. I: 1750-1880, 52.

Stewart & McCann, The Educational Innovators Vol. I: 1750-1880, 51.

Stewart & McCann, The Educational Innovators Vol. I: 1750-1880, 51-52.

See David Williams, A Treatise on Education.

Stewart & McCann, The Educational Innovators Vol. I: 1750-1880, 31.

Eric Robinson, “R. E. Raspe, Franklin's ‘Club of thirteen’, and the Lunar Society,” Annals of Science, Volume 11, Issue 2, 1955, https://doi.org/10.1080/00033795500200145.

Stewart & McCann, The Educational Innovators Vol. I: 1750-1880, 37.

Stewart & McCann, The Educational Innovators Vol. I: 1750-1880, 268.

Stewart & McCann, The Educational Innovators Vol. I: 1750-1880, 31.

Rousseau cited in Allan Bloom, The Closing of the American Mind, 189.

Isaiah Berlin, Freedom and Its Betrayal, 47-48.

Isaiah Berlin, Freedom and Its Betrayal, 52.

Allan Bloom writing in Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Emile or On Education: Introduction, Translation, and Notes By Allan Bloom, 5.

Allan Bloom, The Closing of the American Mind, 299.

Allan Bloom, The Closing of the American Mind, 307.

Allan Bloom, The Closing of the American Mind, 197.

Enjoyed this read!

Relevant video on the Noble Savage I think you’d like

https://youtu.be/7rK2_xqgjvo